FLood2: Turbulence Characterization with the Lambda-2 Criterion

As I wrapped up my undergrad in chemical engineering and computer science, I had the opportunity to work as an undergraduate researcher in a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) group.

This post is meant as a brief, 5-minute overview of that work. It highlights the motivation behind the

This was my first exposure to true distributed computing. In the end, I have a novel contribution to the CFD field, and an algorithm that distributes across hundreds of cores.

Identification and subsequently visualization of vortical structures is fundamental for characterizing coherent motions within complex flows. Most detection methods are based on the velocity-gradient tensor, J, including the Lambda 2 method, which is the backbone of the algorithm being showcased in this section.

This transformation matrix can uniquely decomposed into two physically distinct components: a symmetric strain-rate tensor, S, and an antisymmetric rotation-rate tensor, Ω:

Physically, the symmetric strain-rate tensor represents fluid deformation associated with stretching and compression without rotation, whereas the antisymmetric rotation-rate tensor represents the pure rotational motion of the fluid.

Under the assumptions of incompressibility, negligible viscous effects, and negligible irrotational straining, the Navier-Stokes equations simplify in a way as to allow the second-order tensor combination:

to directly correlate with the existence of a local pressure minimum, which is a necessary but not sufficient condition for a vortex core.

The symmetric strain tensor admits only real eigenvalues, and thus positive and real eigenvalues for the square. Conversely, the antisymmetric rotation tensor results in up to two imaginary eigenvalues, which become negative and real when squared. So, the combination of the squares of these two tensors results in a symmetric tensor whose eigenvalue signs are determined by whether the stress or rotation eigenvalues had the greater magnitude.

By taking the eigenvalues and sorting them:

with

the second eigenvalue

The magnitude of the second most negative eigenvalue is directly proportional to the strength of rotation relative to strain; a more negative

Algorithm Development and Analysis

To address the inherent subjectivity and limited quantitative capabilities of the conventional

The FLood2 algorithm initially computes the

Additionally, the quantitative analysis requires computation of the cell volumes. For fully structured hexahedral meshes, each hexahedral cell volume is calculated by decomposing the cell into a set of tetrahedra whose volumes are computed via the scalar triple product. Given the consistent vertex ordering guaranteed by the VTK standard, this decomposition and volume computation is straightforward and unambiguous.

The core of the FLood2 algorithm uses a breadth-first search (BFS) flood-fill. First, an adjacency map is created, identifying neighboring cells based on the number of shared vertices. In structured hexahedral meshes, two cells are neighbors if and only if they share exactly four vertices.

For each

Since FLood2 must examine every one of the

Running in Parallel

A significant advantage of the FLood2 algorithm is its inherent parallelizability. First, the

To achieve spatial parallelism within a threshold, the computational domain can be partitioned into non-overlapping subdomains by graph partitioning. Each subdomain, or rank, is assigned to one process or thread. Within its subdomain, the worker only performs BFS on its owned cells, and assigns unique island IDs. This generates a set of local vortex islands labeled independently in each partition. Because subdomains are disjoint, these BFS traversals can be done concurrently without race conditions.

Because vortices can cross partition boundaries, local islands that touch across ranks must be merged. This is done by recording an equivalence relation: if a boundary cell in rank A’s island a is adjacent to a boundary cell in rank B’s island b, then we record the equivalence:

In other words, these islands are part of the same global vortex if they contain any face-connected cells. These equivalences form a graph connecting local island IDs across ranks. To resolve equivalences, a distributed union-find algorithm is applied. This process assigns a single global component ID to every island such that islands spanning multiple partitions are stitched into one vortex. Finally, each rank contributes its partial volume and centroid moment sums for its owned cells, keyed by the global component ID; a global reduction then produces the total volume and centroid of each stitched vortex.

SZ Geometry Turbulent Flow Characterization

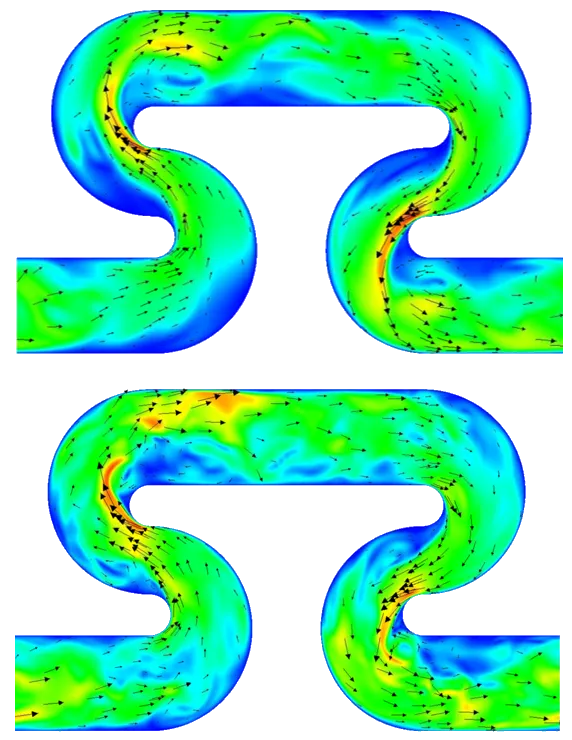

This algorithm was tested on a turbulent flow in the SZ geometry. Based on the velocity magnitude contours of cross-sectional slices, Reynolds numbers of 500 and 1000 create enough turbulent structures for a proper analysis.

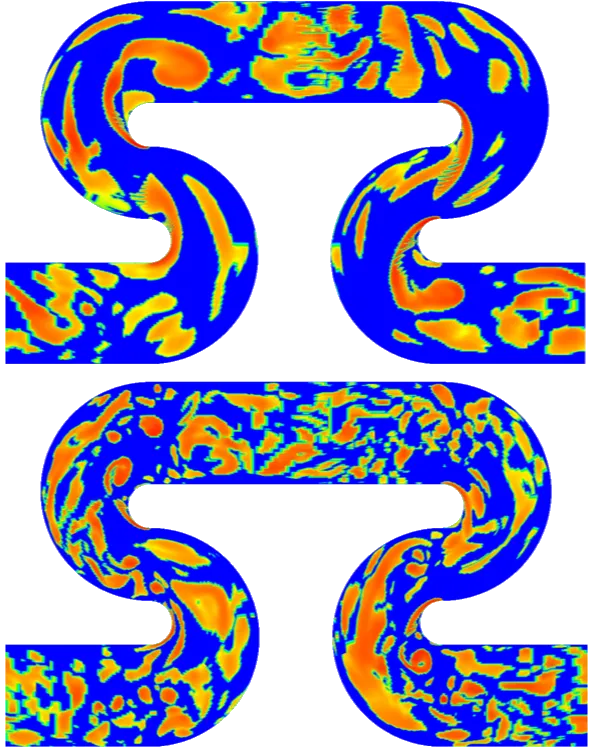

Likewise, after filtering out all positive

Quantitative Analysis using FLood2 Algorithm

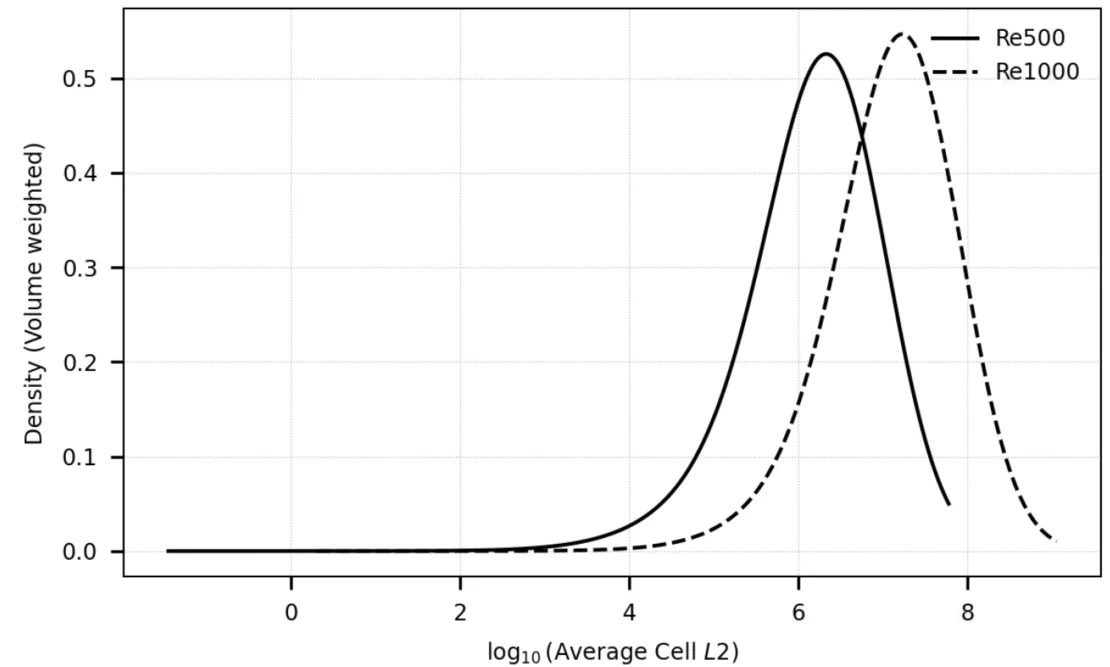

Initial distributions of volume-weighted

The skew in the distributions reflects the fact that large, high-energy eddies fragment into smaller structures more quickly than the reverse process, so very strong vortices are rarer, suppressing the upper tail. A slight reduction in standard deviation was also noted at Re = 1000. Most importantly, these distributions help decide the range of lambda values to sample FLood2 across; in this case, a range of

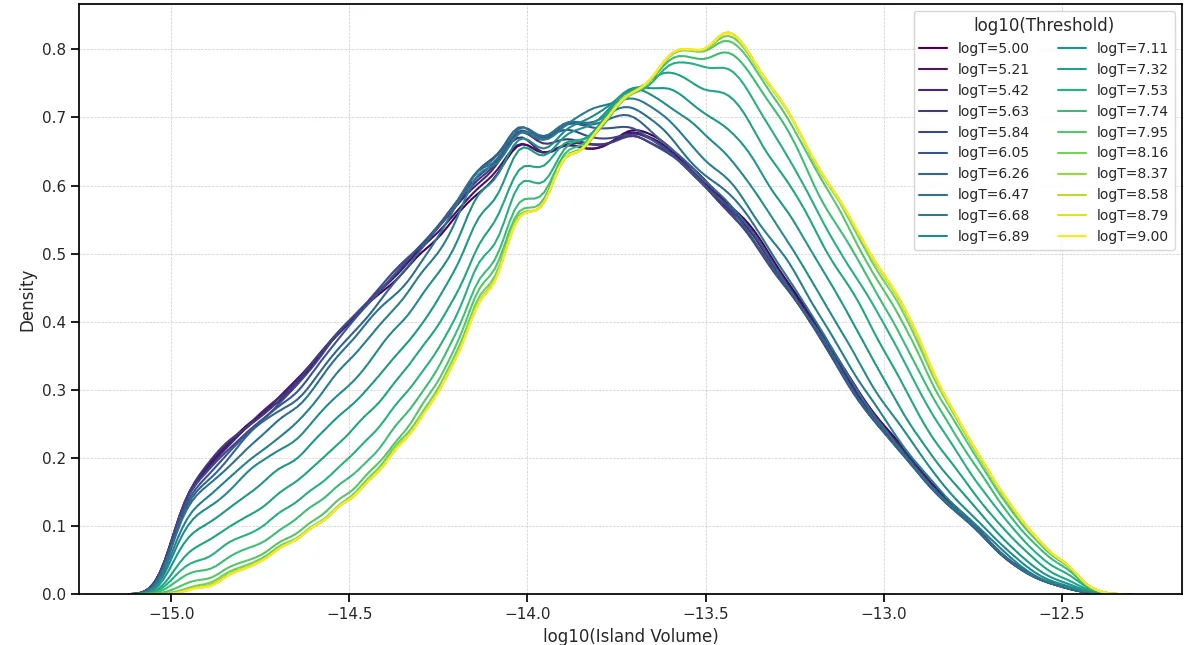

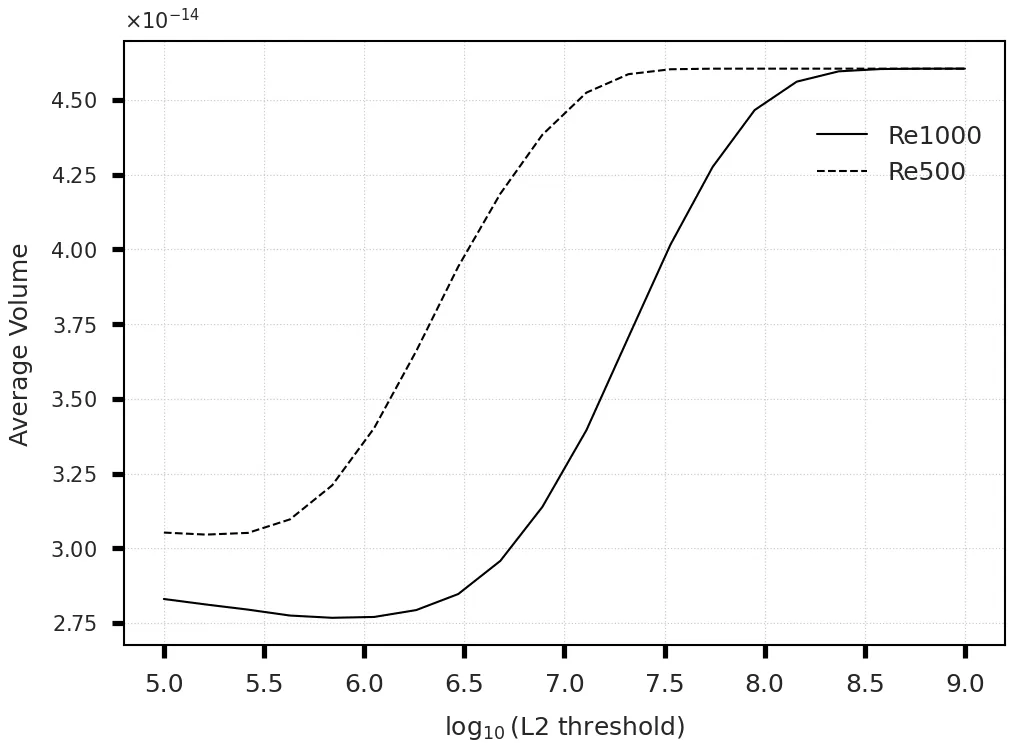

Analyzing the relationship between the average vortex volume and

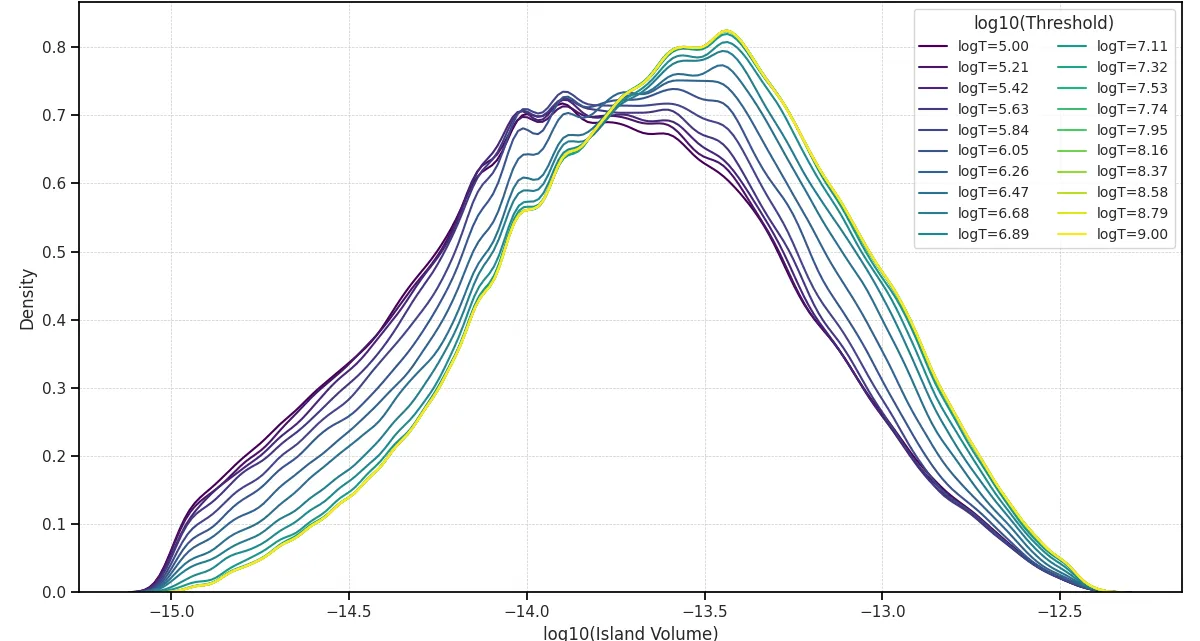

Looking at the distribution of vortex volumes within a single Reynolds number rather than simply tracking the average across Reynolds numbers also provides valuable insight. The distribution of vortex volumes at Re = 500 shows a progressive shift toward larger average sizes as the

Increasing Reynolds number from 500 to 1000 altered the vortex size distribution by broadening and shifting it towards larger vortices at lower